A browser-based, real time collaborative programming platform that makes working with others on small pieces of code easy, spontaneous, and convenient.

Multiple programming languages supported.

Try it out here.

Umbra is a browser-based code editing and evaluation tool for quickly and seamlessly collaborating on code in real time.

Umbra makes it simple for remote collaborators to program together. The workflow setup consists of three steps:

Navigate to the Umbra homepage,

Copy the room URL and send it to teammate(s),

Paste in some code, or start together from scratch.

At this point, users have access within a single browser window to real-time collaborative editing, secure code evaluation, and support for multiple programming languages.

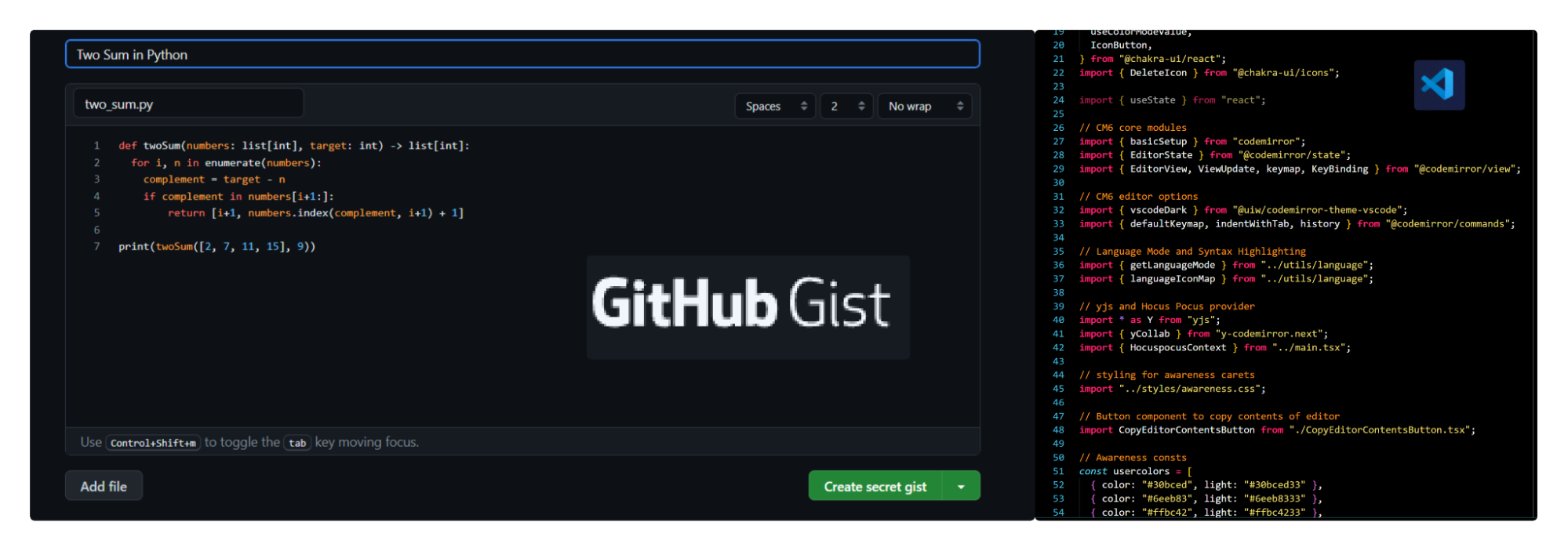

With the optional creation of an Umbra account, users also gain the ability to save pieces of code in a personal library for later use. This provides a degree of convenience without necessitating the weight of a full browser-based IDE.

Umbra’s code library functionality

For those learning to write code for the first time, or for seasoned developers learning a new programming language, it can help to share code with someone who has more experience with that language. Learning foundational programming concepts, or trying to understand the nuances of a new language’s syntax, can be made easier and more effective with live mentorship and feedback.

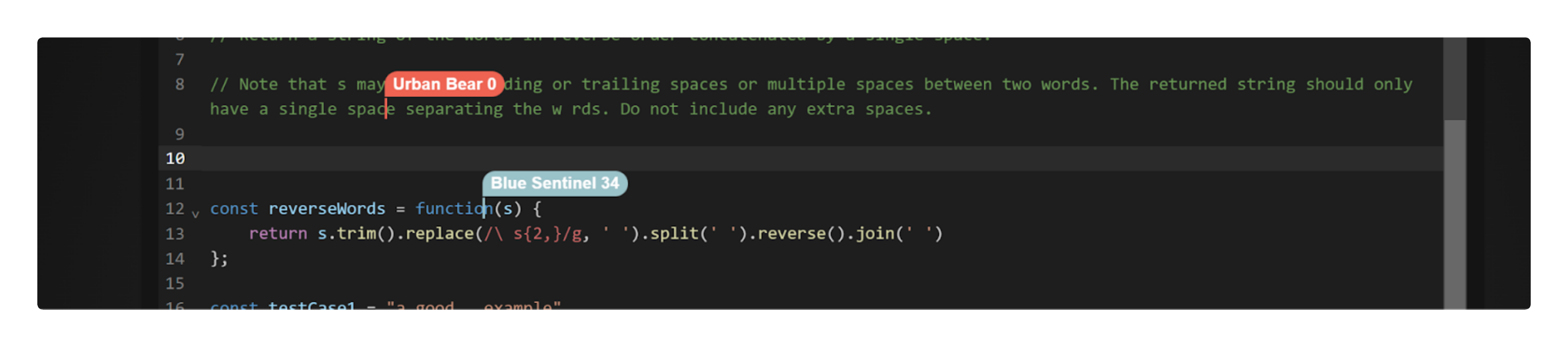

The ability to program in real time with other people—when multiple cursors and name labels provide “awareness” of what others are doing—is a more mentally stimulating and engaging experience than sharing code by copying and pasting. It is possible to get feedback by showing someone a static, un-runnable version of the code, but being able to let them edit it in tandem and view the evaluation results live is a more interactive, engaging, and social teaching-learning experience.

In addition to being used as a code sharing, teaching, and learning tool, Umbra is also useful as a coding interview platform for smaller-scale companies as an immediate, no-fuss access to a collaborative coding environment.

We designed Umbra to be as fast and pain-free as possible for users to share, teach, and learn by writing and evaluating snippets of code in pairs or small groups of collaborators, as if they were working together in the same room.

Umbra is a good option where users do want to edit and run code together in real time, but where a complete IDE experience is unnecessary. It does not provide features such as a terminal or a browser-based file system, so it is not suitable for collaboration on a full-fledged software project. Instead, it is ideal for spontaneously collaborating on individual files, functions, or specific pieces of code logic.

The primary focus of Umbra is to make pair and group programming quick and convenient in situations where people may otherwise send each other non-runnable, non-editable code, or might unnecessarily opt for the full clout—and heftier setup procedures—of a collaborative IDE.

Sharing unrunnable ‘dead code’ snippets or using a full IDE aren’t always the best ways to collaborate

In our initial research, we were fascinated with real-time collaborative editing and the recent flourishing of engineering innovation in this domain. We envisioned a tool akin to Excalidraw or Google Docs, but for programming—including the ability to evaluate code and view the results directly in the browser.

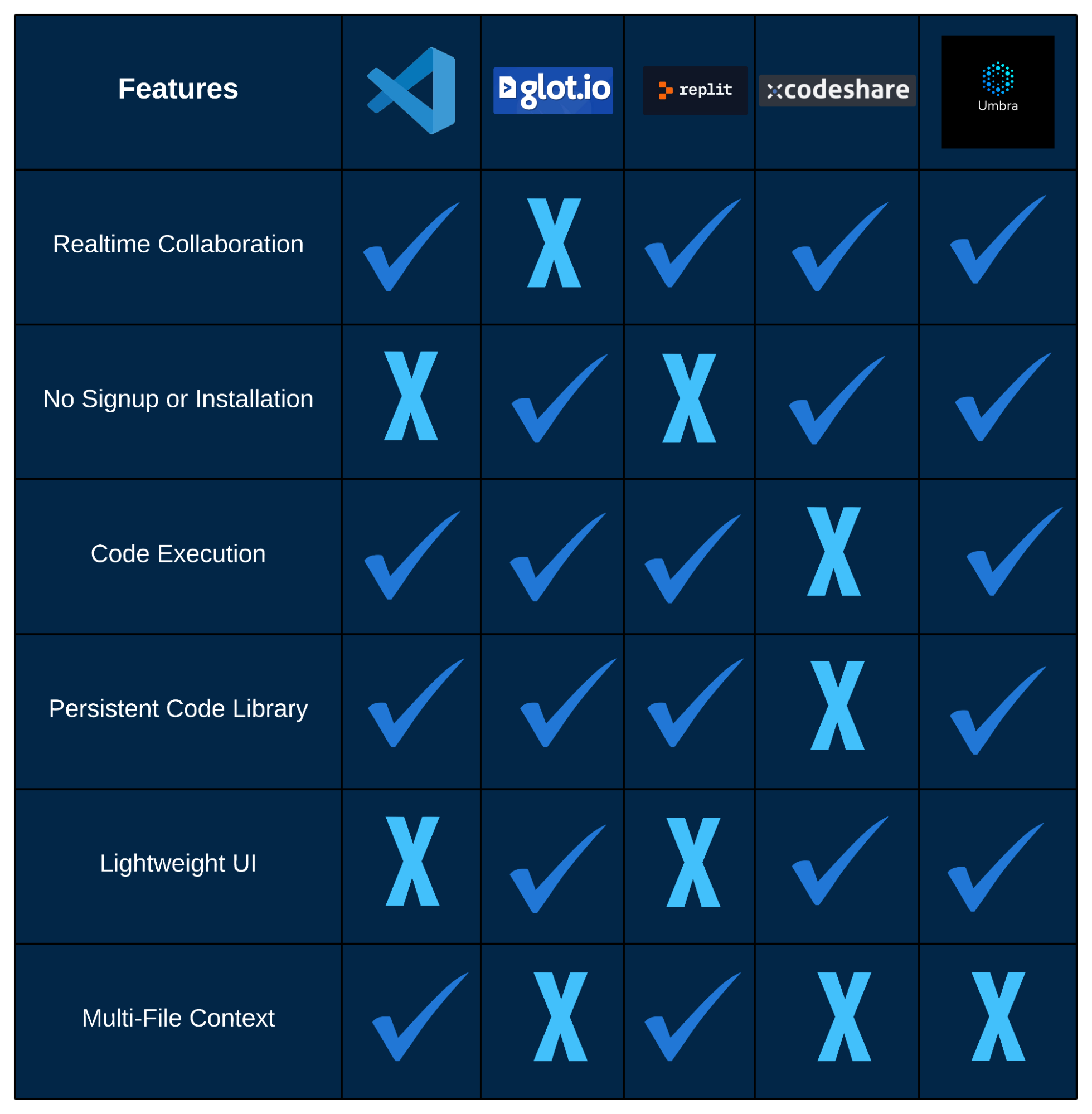

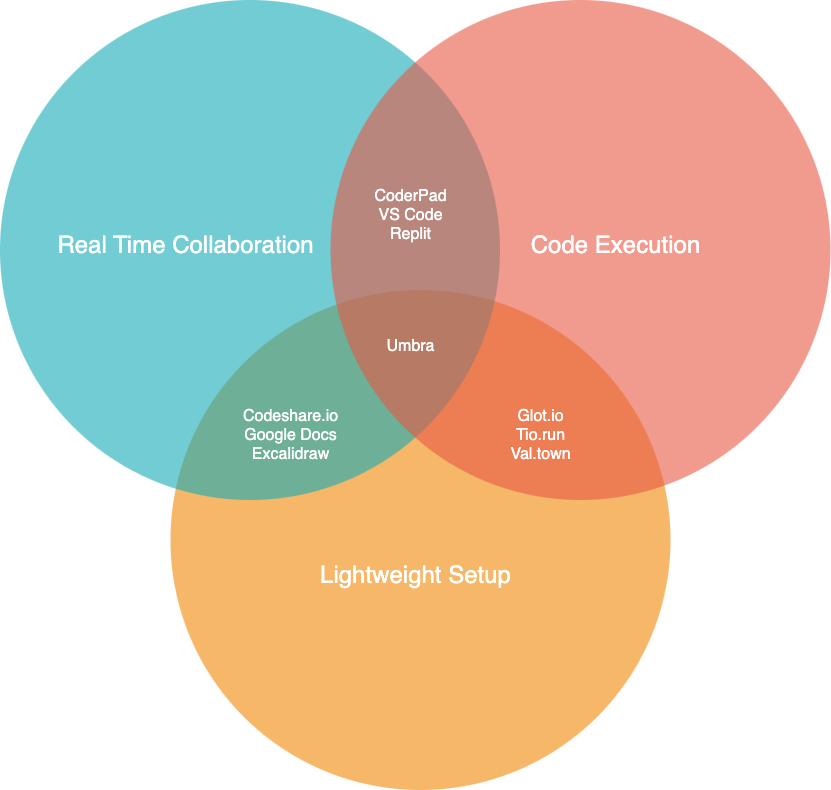

The existing solutions we found tend to fall into one of three categories:

The factors in the last category are acceptable for use cases that require a set of IDE-like features. However, given the simplicity and spontaneity of the use case we’re targeting, having so many setup considerations almost defeats the purpose. Because of this, there are still many situations in which both students and professionals find themselves copying and pasting code to each other, or screen-sharing, rather than using an online compiler or IDE.

Umbra as it relates to other web applications in this space

Umbra sits in the middle zone to facilitate use cases such as debugging a function, sharing approaches to refactoring a block of code, or helping someone prepare for a technical interview—any occasion that can benefit from real-time multiplayer editing and code evaluation, and where shared access to a larger IDE-like environment is less essential than being able to collaborate spontaneously.

The phrase real time collaboration encompasses a broad set of scenarios in which users contribute mutually to some form of shared data store. In order to better illustrate what we set out to accomplish with Umbra, we will take a closer look at the terminology.

In the context of the web, real-time refers to users’ experiences of latency: as long as the time delay between an event and a user’s perception of the event is small enough, the user will perceive the change as instantaneous. One example of real-time behavior on the web is that of data update feeds: users can view changes in metrics such as weather data, stock prices, or transport statuses in a way that seems to immediately reflect what’s going on in the physical world.

Collaboration, meanwhile, refers to multiple users engaging with the same medium. Generally speaking, collaboration over the web can happen in many ways, and it is not always synchronous. For example, multiple contributors to the same GitHub repository are engaged in collaboration with each other, but they are not collaborating in real-time. Instead, contributors handle conflicting changes by making pull requests and resolving conflicts manually.

In a real-time collaborative editing application, the goal is to mimic the experience of working with others simultaneously—as if in the same physical room, or on the same computer. The main technical challenges of this goal involve resolving conflicting changes, broadcasting awareness data, and minimizing the latency of updates. Let’s take a closer look at what each of these mean:

Two users working in the same document at the same time

A collaborative editing application is a kind of distributed system, where there are several replicas of shared data: each user has access to their own copy of the shared document.

Since users are free to make changes to their copy at any time, temporary inconsistencies between these copies are inevitable. The keyword is temporary, though; in order to create a robust real-time collaborative application, we need a way to ensure that all user copies will eventually converge to the same state.

We came across two industry standards for implementing eventual consistency in collaborative editing: operational transformation (OT) and conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs). Both are used in industry-scale collaborative editing applications. However, we chose to proceed with CRDTs for a few key reasons:

Both approaches are the subject of a large amount of research; a complete review and comparison of them is beyond the scope of this case study, but we will provide a brief overview as context for the decisions we made.

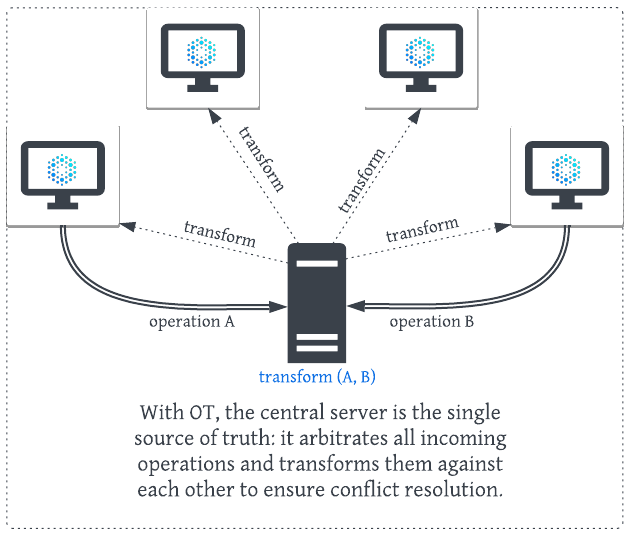

Operational transformation relies on a central server that functions as a moderator between all active clients. The server collects all changes to the document, applies them in an order of its choosing, and returns the results to the clients.

Essentially, there are three factors that govern the order in which user changes get applied in the OT model:

An important consideration with OT is that a central server is required to arbitrate changes, and this leads to a potential single point of failure. It may also lead to inconsistencies in the event of server downtime or network issues. On the other hand, a decentralized (CRDT-based) approach facilitates horizontal scalability, as the system can distribute the load across multiple replicas without a centralized bottleneck.

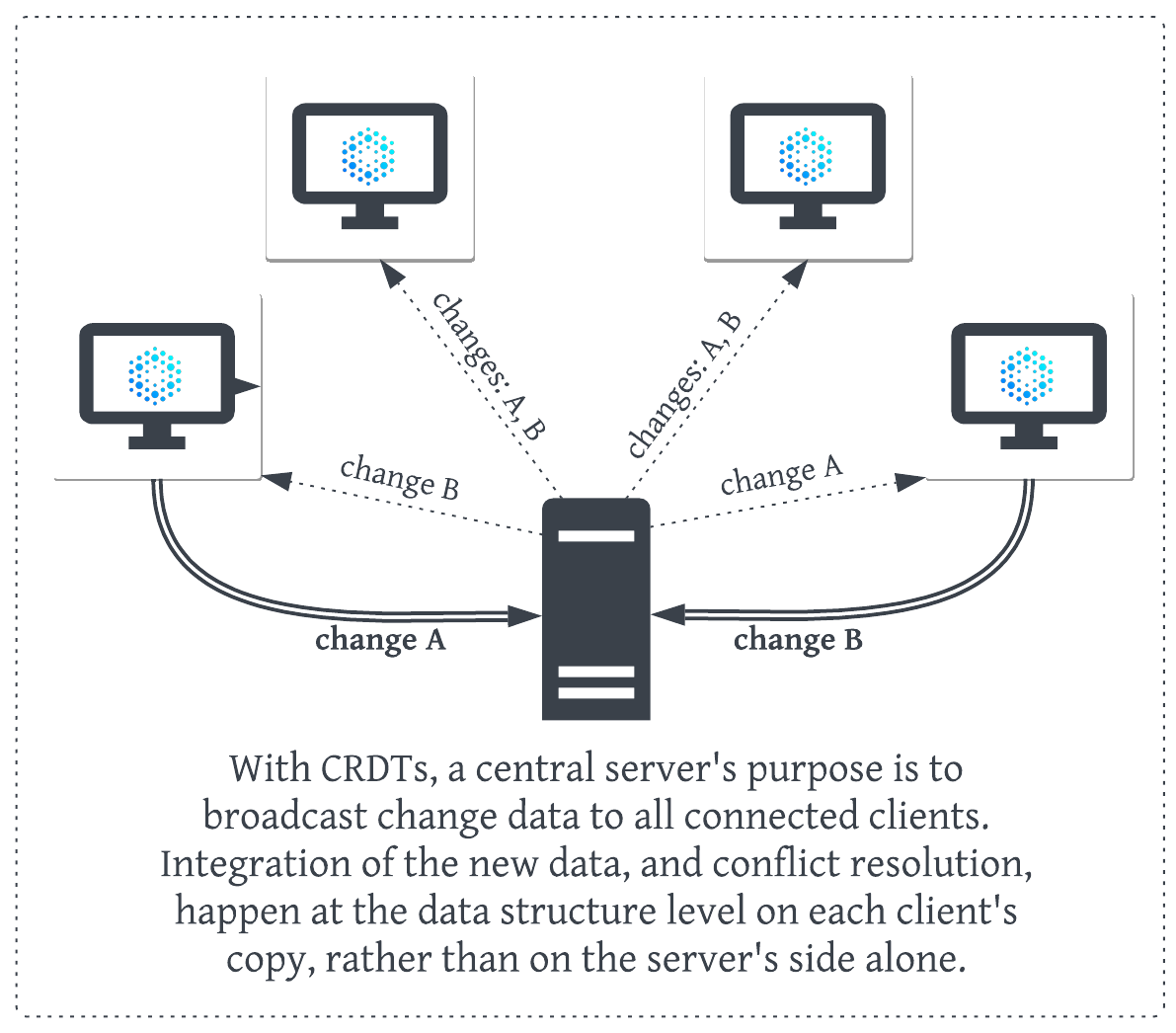

CRDTs are similar to OT in that they also provide a way for multi-source document changes to be applied sequentially. However, they differ in that conflict resolution is “baked in” to their structure, which eliminates the need for a centralized server. CRDTs accomplish this by adding some additional complexity to the underlying data structures that represent users’ changes.

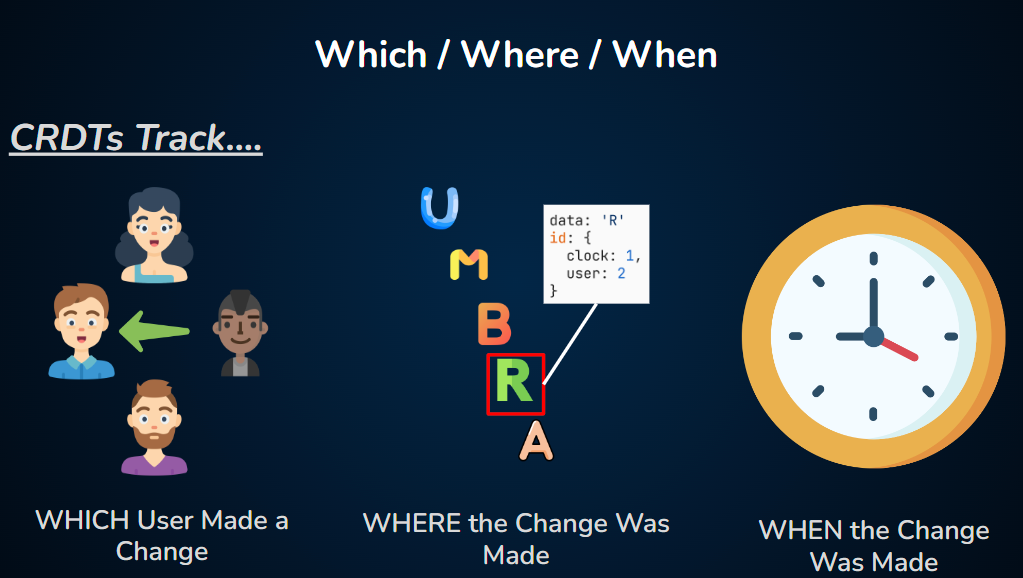

As with operational transformations, CRDTs track which user made a change, where in the document they made it, and when they made it. In addition, though, CRDTs assign each change a set of globally unique identifiers that further define its context and content.

This ensures that change events will be both commutative (successive changes will lead to the same result, regardless of the order in which they are applied) and idempotent (duplicate operations—such as two users trying to delete the same character—will not result in unwanted extra operations).

With CRDTs, all conflict resolution logic happens algorithmically, without a central arbitrator calling the shots.

The tradeoff—and one of the major criticisms of CRDTs—is that they involve significant memory and processing overhead. For example, each newly inserted character in a text document may be given its own unique ID. If ever a user deletes a character, it actually stays in memory; it’s just “marked” as deleted. Memory usage can accumulate significantly this way, particularly in large documents with frequent edits.

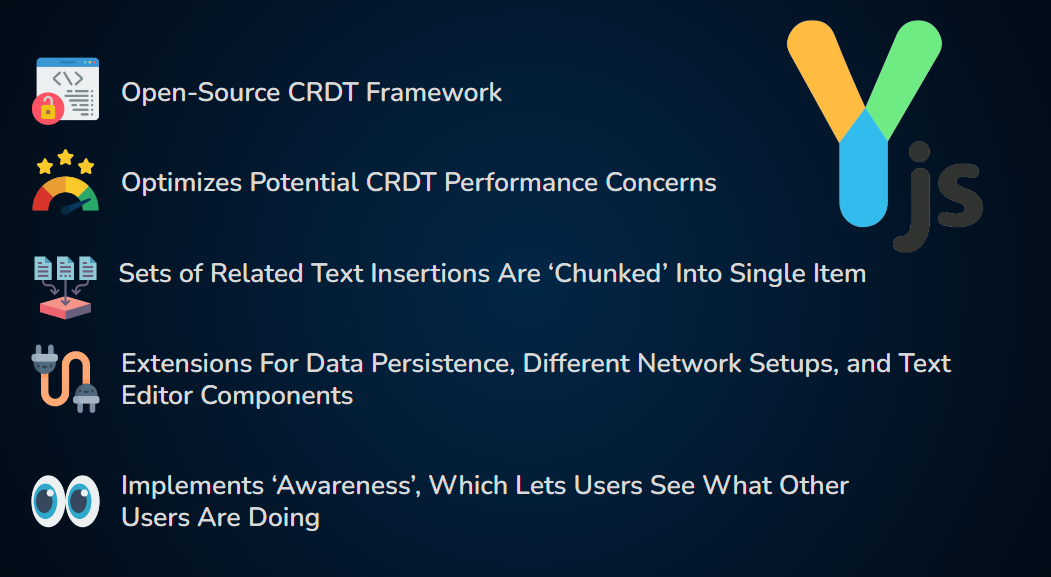

While the decentralized nature of CRDTs was appealing, we wanted a way to offset potential performance concerns associated with high memory and processing needs.

This led us to discover Yjs, an open-source CRDT framework that provides a degree of optimization under the hood: large sets of related text insertions are essentially “chunked” into a single aggregate change item. This leads to better performance with regards to operational cost and memory usage.

Yjs is not without its caveats: it is a relatively young technology, with several experimental elements. There are some outstanding improvements yet to be made; for example, it has been shown that with large numbers of clients (>10,000) on a given document, Yjs transactions can take up to 2 milliseconds each, which is quite slow. However, this was not a necessary consideration for Umbra’s use cases.

Yjs was created specifically with real-time collaborative text editing applications in mind, and comes with a thriving ecosystem of extensions for several different network setups, data persistence options, and text editor components (see Section 3).

In the prototypical CRDT model, each new character that a user types is assigned a unique ID and other metadata. In Yjs, multiple consecutive insertions (including copy-paste events) are merged into a single change item. This significantly reduces the number of new data objects created, and therefore lessens memory load.

Once there is a working setup for sharing and synchronizing CRDT-based shared document state, the stage is also set for managing awareness. In Yjs, awareness updates are also implemented as CRDTs under the hood, and are propagated between nodes in a similar way. The Yjs y-protocols module, which we will encounter in Section 3, offers protocols for syncing awareness information alongside document updates.

The performance optimizations that Yjs provides have a positive effect on latency. Additional factors influencing users’ perceived time lag are the choice of networking paradigm, and the physical distance between clients and servers.

In the next section, we’ll take a closer look at the technologies we chose for handling these factors. We will also dive further into the inner workings of Yjs, how we used it to implement collaborative editing, and what it took to integrate it into our application.

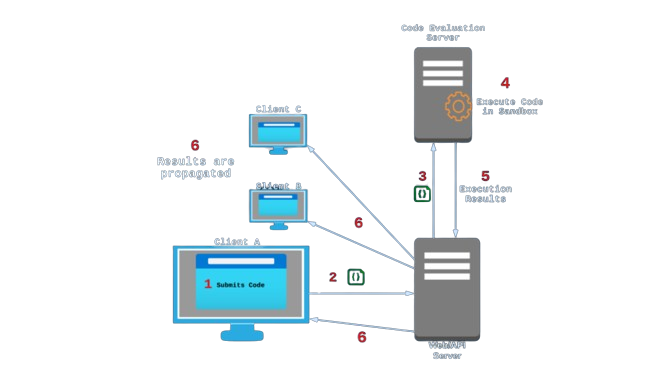

Our real-time collaboration implementation involved establishing persistent connections, integrating Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs) with our chosen code editor component, CodeMirror, and managing multiple WebSocket “rooms”. Each “room” in this context represents a shared document that multiple users can edit simultaneously.

We leveraged Yjs’s y-codemirror.next module to handle undo/redo actions and cursor position awareness in a collaborative environment. The choice of WebSocket over WebRTC was made for its simplicity, reliability, and ease of data persistence.

In the following sections, we will delve into the specific challenges we faced in building our real-time collaboration backend and the solutions we considered. We will also discuss our decision to use Y-Sweet, a suite of components that extends some of Yjs’ networking functionality, and adds additional features such as data persistence and deployment on Cloudflare’s edge network.

When designing our collaborative code editor, we had to decide between two main technologies for real-time communication: WebRTC and WebSocket. Both provide protocols and APIs, each with their strengths and trade-offs.

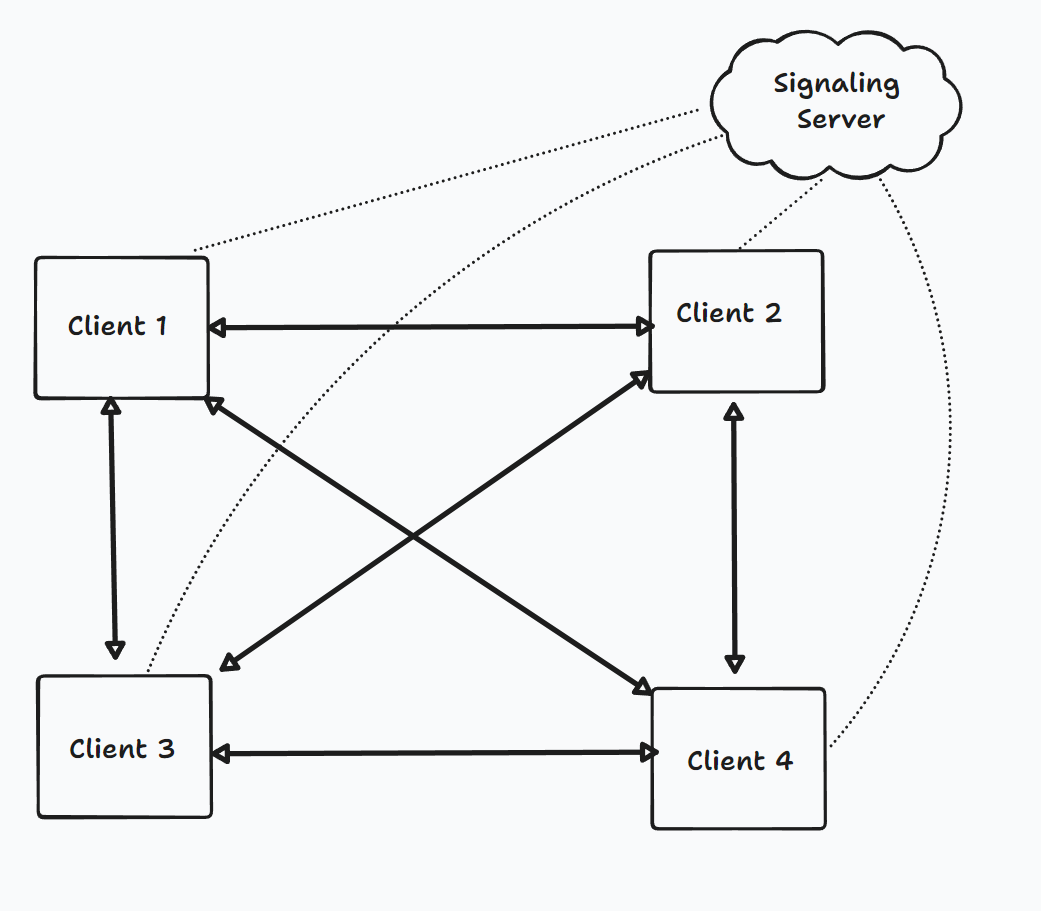

WebRTC offers a peer-to-peer (P2P) protocol, where data is transmitted directly between users, and is primarily used over UDP for low latency. It’s ideal for scenarios where users are geographically close, as it establishes direct connections, potentially reducing latency. However, its P2P approach introduces complexity in connection management, presents scalability issues due to quadratic growth of connections, and lacks built-in data persistence.

In a P2P architecture, every user is connected to every other one

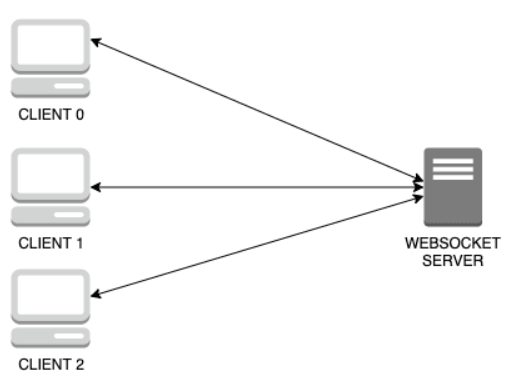

WebSocket provides a client-server communication protocol that works on top of TCP, and enables bidirectional communication between the client and the server. It’s easier to set up and manage compared to WebRTC due to TCP-based operation and fewer NAT/firewall issues. It’s also better suited for larger networks, as the number of connections grows linearly (as opposed to quadratically) with the number of peers. However, all data goes through a central server, which can increase server load and operational costs, potentially resulting in higher latency, and raising data privacy concerns.

After weighing the benefits and trade-offs of both protocols, we decided to use WebSocket for our application. This decision was influenced by our need for scalability, simplicity in connection management, and data persistence. It should be noted that Yjs also allows “meshing” of providers—meaning that we could use both WebSocket and WebRTC providers simultaneously and Yjs would simply use the first update received. This could potentially allow us to gain the benefits of both approaches, but for simplicity we opted for just WebSocket.

The backbone of our WebSocket implementation makes use of y-websocket, a Yjs module that wraps around the WebSocket protocol and integrates it with y-protocols to provide syncing and awareness utilities. We will delve deeper into this functionality in 3.4 Connection Providers. For the discussion that follows it should be noted that ultimately we chose to use an open source project (“Y-Sweet”) which extends y-websocket, which we will talk more about in section 3.5.

Note: While we’re discussing the functionality provided by y-websocket, it’s important to remember that we’re actually using Y-Sweet in our application. Y-Sweet extends y-websocket, so it includes all the features of y-websocket discussed here, in addition to its own unique features.

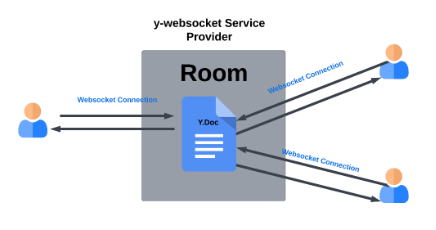

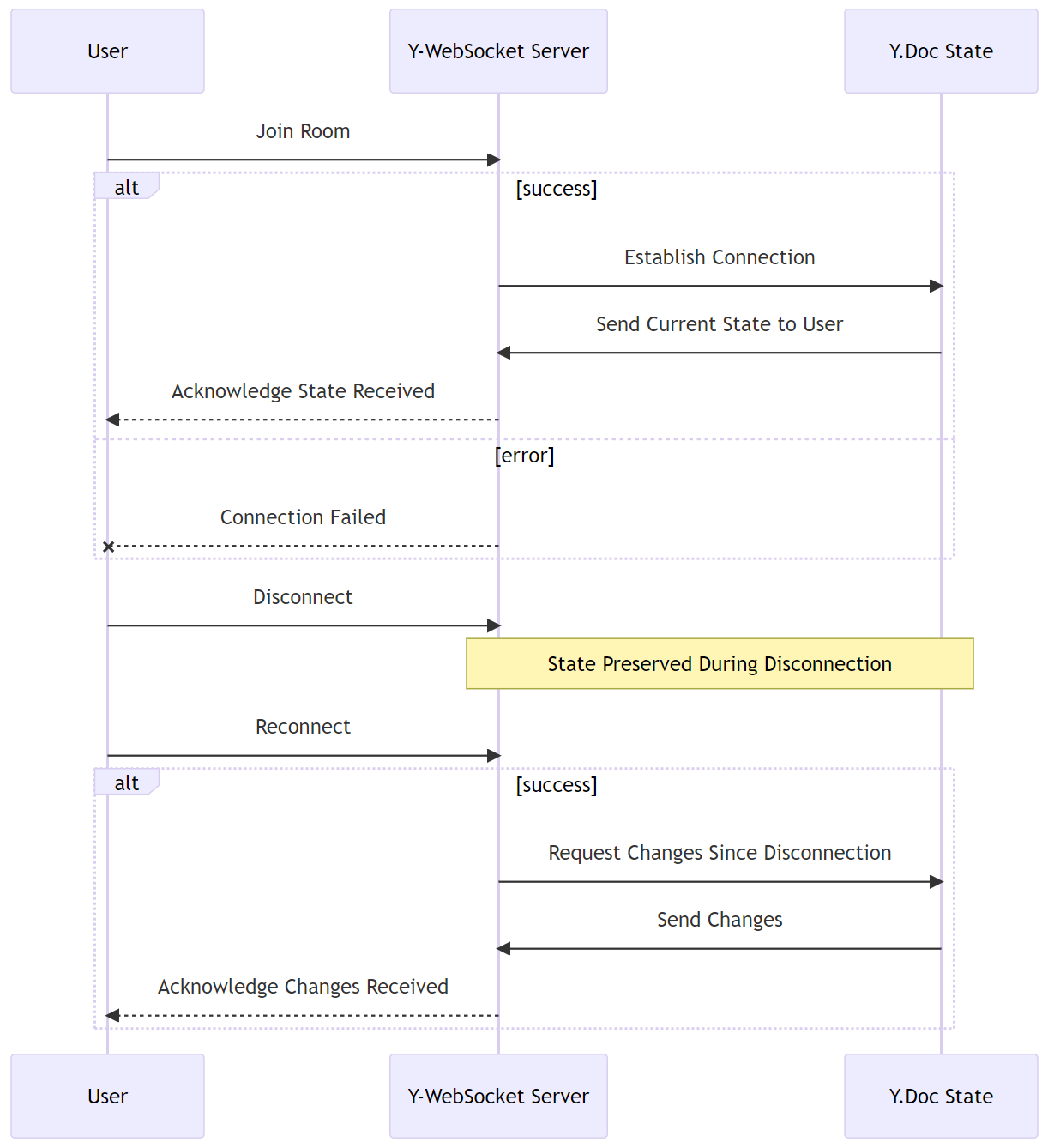

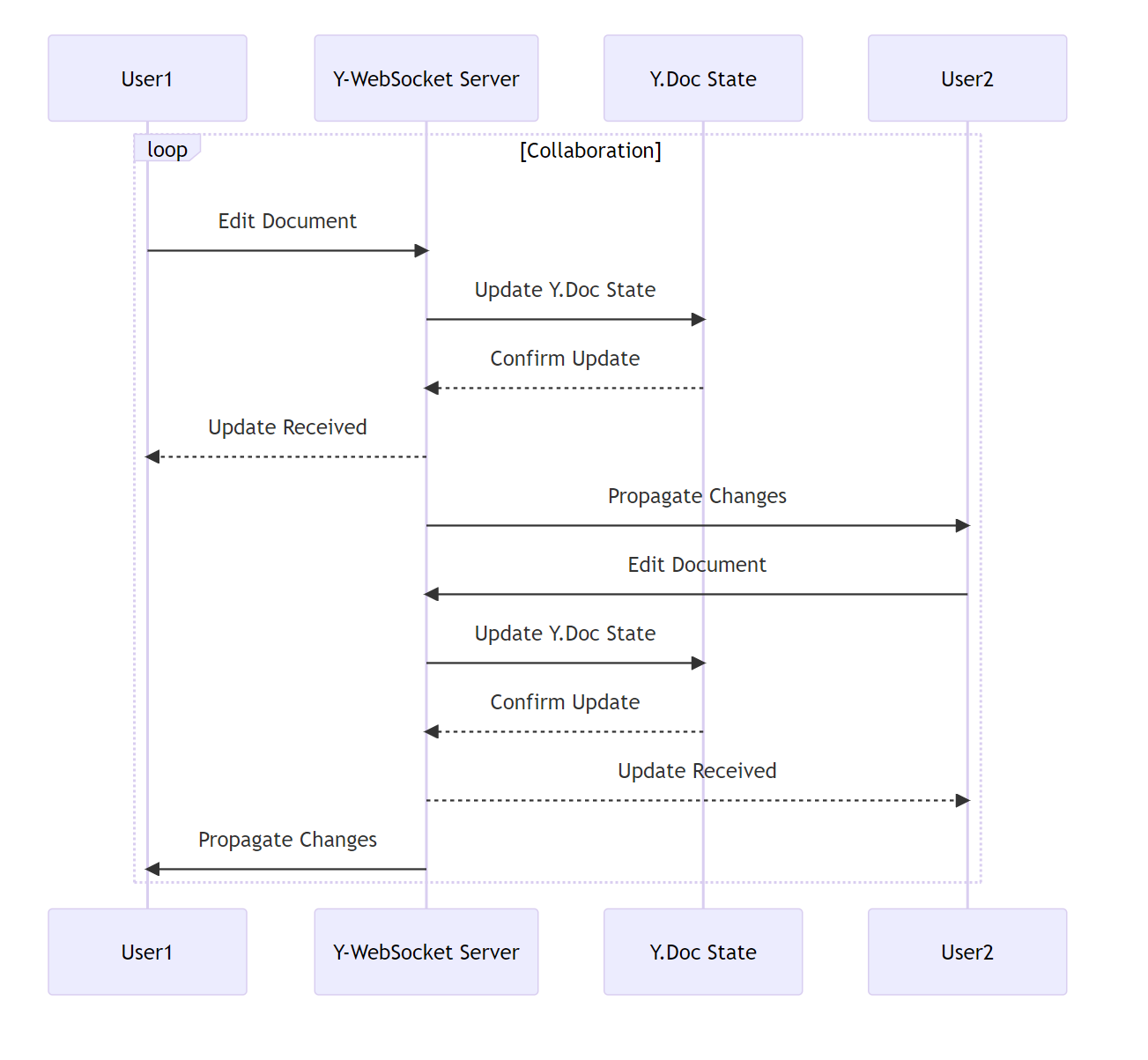

In our application, we use y-websocket as our connection provider. It plays a crucial role in managing WebSocket connections, synchronizing the state of the shared document across all users in a room, and handling room management and user presence.

In the context of our application, a “room” corresponds to a single Y.Doc. A Y.Doc is the top-level shared data type in Yjs, which contains all the shared data and state for a collaborative session. Each Y.Doc represents a shared document, and all users connected to a specific “room” are collaborating on the same shared document.

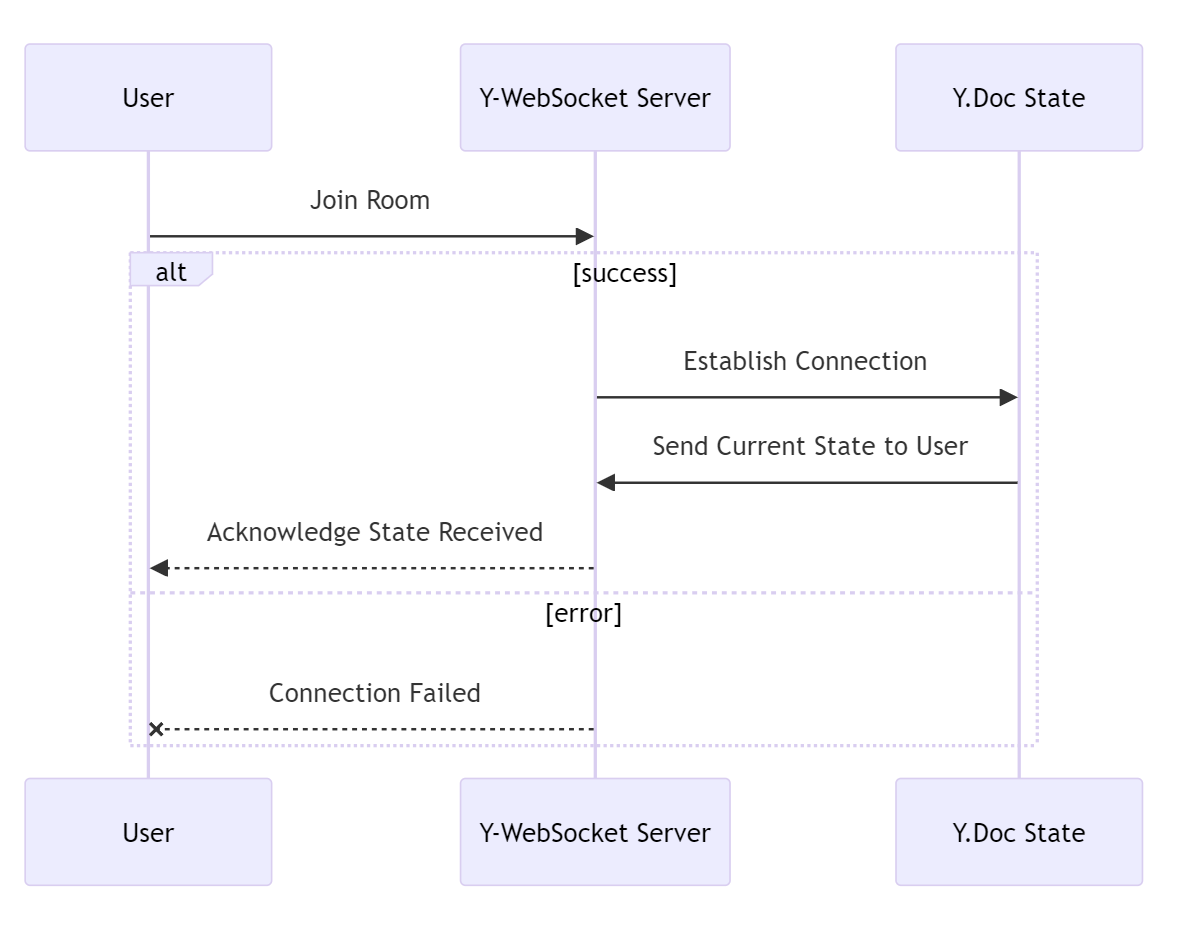

On the client side, y-websocket is responsible for establishing a WebSocket connection with the central server when a user joins a room. This connection encapsulates a shared document, represented as a Y.Doc.

On the server side, y-websocket manages all active connections. It listens for changes in each Y.Doc and propagates these changes to all users in the corresponding room.

y-websocket also integrates with y-protocols to provide syncing and awareness utilities:

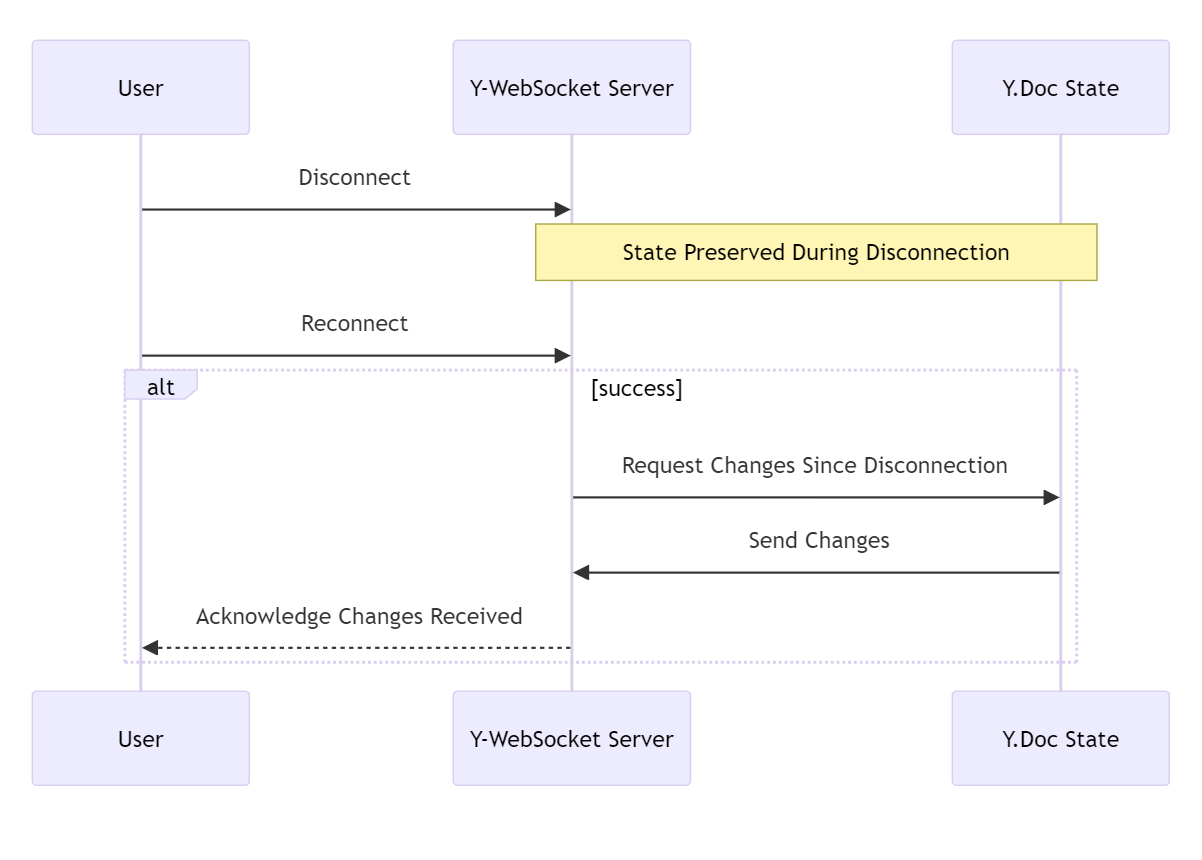

sync protocol ensures that all users have a synchronized view of the shared document. It listens for changes in each Y.Doc and propagates these changes to all users in the corresponding room.y-codemirror.next integrates with CodeMirror to provide awareness updates. The next step is that the awareness protocol propagates the updates to all users in a room.The lifecycle of a WebSocket connection begins when a user joins a room. y-websocket establishes a connection and sends the current state of the shared document to the user. If a user disconnects, y-websocket handles this event and ensures that any changes that occurred while they were disconnected are sent to them when they reconnect.

Data flows from one client to another through the WebSocket server and y-websocket. When a user makes a change to their Y.Doc, y-websocket propagates this change to all other users in the room. This ensures that all users always have a synchronized view of the shared document.

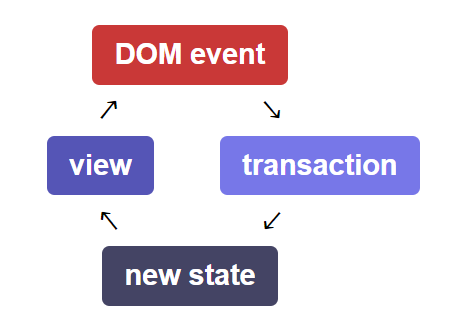

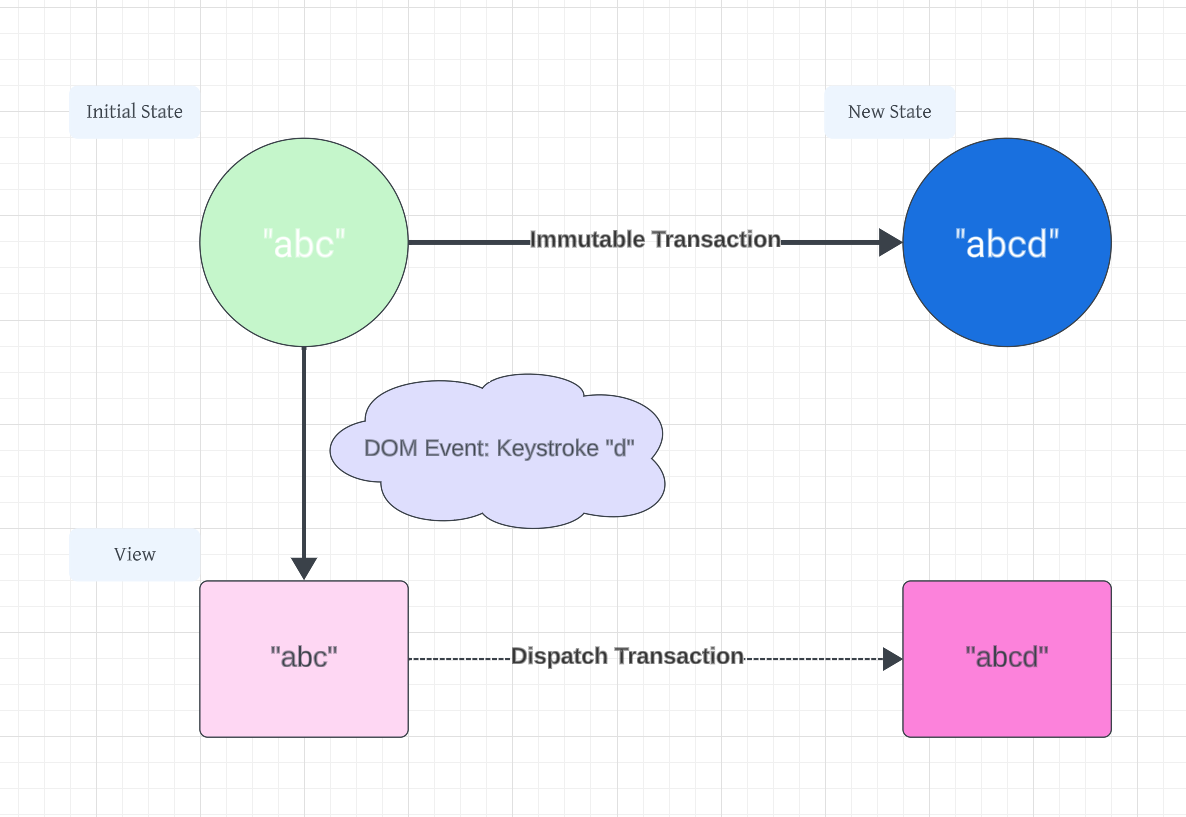

In our React Single Page Application, we use CodeMirror for text editing. CodeMirror is a code editor component for the web that manages its own state independently of React. User inputs, such as keystrokes, are processed as transactions within CodeMirror. These transactions are then synchronized with Yjs via the y-codemirror.next module, enabling real-time collaborative editing.

CodeMirror maintains its own internal state, which includes the content of the editor and cursor positions. User inputs, like keystrokes, are handled as transactions that update the EditorState. These transactions are then dispatched to the EditorView, which synchronizes its DOM representation with the new state, ensuring that the user interface accurately reflects the current state of the editor.

Say we had an initial document “abc” with the cursor after “c”, and then we typed the letter “d”. This DOM event would be received by the View, turned into the transaction {changes: {from: 3, insert: "d"}, and dispatched to create the new EditorState “abcd”, which the EditorView would then synchronize its DOM representation to display.

The y-codemirror.next module binds Yjs’s Conflict-free Replicated Data Type (CRDT) functionality with CodeMirror. There are two main components to this binding:

y-codemirror.next module also manages undo and redo actions so that they only affect the user who initiated them, rather than reverting or reapplying changes made by others. This supports a consistent and intuitive user experience.It sits between the state of the CM instance and the Y.Doc and keeps their state in sync - keystrokes which update the CM State by transactions as discussed are then translated into transactions which update the Y.Doc state. In the other direction, updates from other clients are received by Yjs and the CodeMirror state is synchronized

Cursor positions and selections are also tracked in the EditorState and shared as awareness information through the y-codemirror.next module. Just as with document changes, y-codemirror.next also listens for changes in cursor positions and selections within the CodeMirror component. These changes are translated into awareness updates, which are then propagated to all other users, allowing everyone to see where others are working in real time.

Building a real-time collaborative application presents several challenges, which extend beyond just managing WebSocket rooms:

We considered several approaches to managing these challenges:

y-websocket would also come with the responsibility of updating our solution as new versions of Yjs and y-websocket are released.y-websocket and offers features like connection management, data synchronization, scalability, and persistence. Moreover, its server is designed to be deployed on a global edge network (Cloudflare’s) for low latency, and is built on Yrs, a Rust port of Yjs, for increased performance.Given our decision to work with Yjs and y-websocket and our concerns around scaling and latency, Y-Sweet emerged as a compelling toolkit which could give us end-to-end developer ergonomics like we might expect to find in a proprietary state-sync platform but without the lock-in, while addressing the challenges we enumerated in 3.5.1.

What is Y-Sweet?

Y-Sweet is a suite of open-source packages designed for developing and productionizing Yjs applications. It consists of three primary components.

y-websocket and uses the Rust port of Yjs, Yrs, to deploy as a WebAssembly module on Cloudflare’s edge. This deployment strategy allows Y-Sweet to leverage Cloudflare’s global network for low latency and high availability. The server also persists document state to AWS S3-compatible storage (either AWS S3 or Cloudflare R2), ensuring data persistence. It scales horizontally with a session backend model, providing robust scalability.By adopting Y-Sweet, we were able to address our key challenges around connection management, data synchronization, scalability, and persistence, while also ensuring seamless integration with our React application.

Evaluating Y-Sweet

Evaluating Y-Sweet along the dimensions that we enumerated as challenges in 3.5.1:

In the previous section, we discussed our decision to adopt Y-Sweet for our real-time collaboration service, highlighting its key features and benefits. Now let’s dive a bit deeper into the technical aspects of how Y-Sweet leverages Cloudflare’s edge network and infrastructure to enable scalability and performance, as well as real-time collaboration. We will also discuss how we ensure data integrity and manage connections, and finally, we will consider some trade-offs related to our chosen approach.

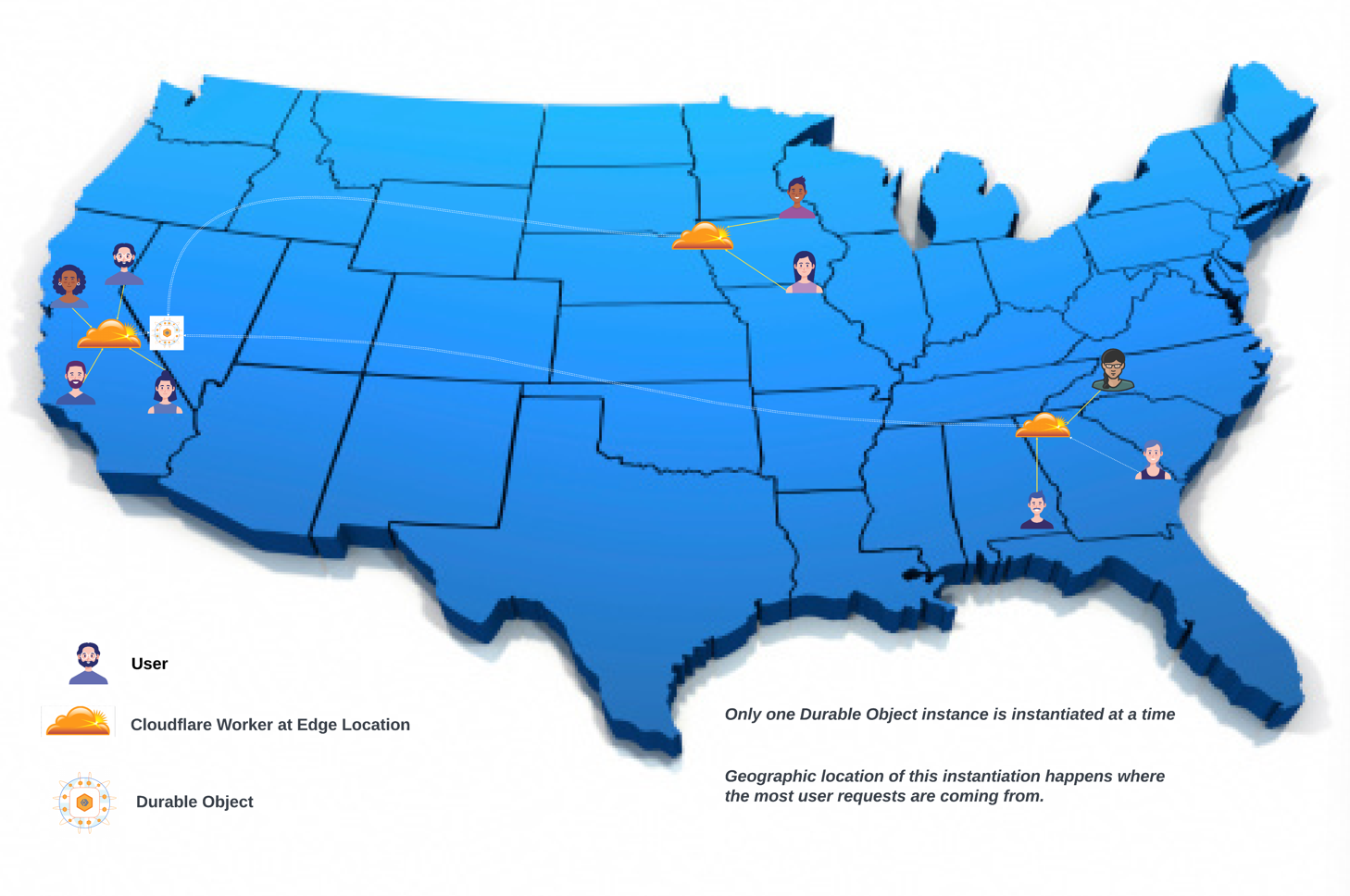

Our application’s scalability is underpinned by the use of Cloudflare’s edge network, which includes Cloudflare Workers and Durable Objects.

Cloudflare Workers enable serverless execution at the Cloudflare network’s edge, which is within 50 milliseconds of 95% of the world’s population. This proximity to users reduces network latency, allowing our application to respond quickly to user interactions.

The problem with using Workers alone for real-time functionality is that Workers do not coordinate between requests. In other words, there’s no way to guarantee that messages from the same WebSocket client will always get connected to the same Worker. This is where Durable Objects come into play. Durable Objects, like Workers, are instances of a particular piece of application functionality. However, unlike Workers or other traditional serverless functions, they have the ability to persist state in memory for the duration of a user session—even if a session involves multiple WebSocket connections from multiple users.

In the context of our application, a “room” refers to a collaborative space where multiple users can interact with the same document in real-time. Each room corresponds to a unique instance of a Durable Object, which maintains the state of the document and handles updates from all users in the room.

The code for a Durable Object is essentially a JavaScript class; for illustrational purposes, it can help to think of Umbra’s collaboration functionality as a class definition, complete with methods that define its interface.

Each time an Umbra user opens up a new room, an instance of this class is created. (For convenience, when we say “Durable Object”, we’ll be referring to an individual instance, rather than the class itself.) This new Durable Object corresponds uniquely to that room. The Durable Object is deployed on the network edge close to the user.

When this user invites collaborators to join, they each connect to a Worker close to them at the network edge. The Workers then route these users (via Cloudflare’s network) to the already spun-up Durable Object. This guarantees that each request or connection associated with a particular room identifier is routed to the same room, and that updates to the document for that room are shared via the correct user connections. In this way, the Durable Object acts as an on-demand WebSocket server.

Durable Objects provide persistent state for Cloudflare Workers

In the simplest possible setup, a WebSocket server would be deployed in a single location, and would be responsible for managing multiple rooms. The rooms would be isolated from each other, but they would all still be running on the same machine.

Now imagine that these rooms are still managed by the same server, but they now have the ability to “fly away” from the machine and “perch” on some other machine farther away. This is essentially what is happening in our setup. The “server” is the Durable Object class we mentioned before. Each room is run on a separate Durable Object instance deployed on Cloudflare’s edge network.

This means that we can create rooms on-demand in any of hundreds of Cloudflare’s data centers around the world, which satisfies our need for horizontal scalability in terms of the number of distinct rooms that can exist at a time.

Moreover, Durable Objects improve application performance by maintaining the state of Y.Doc in memory. This allows for efficient handling of real-time updates, which is crucial for our real-time collaboration service. The initial connection between the client and WebSocket server is typically quite fast, since the Worker is created in the data center nearest to the user. After that, requests are routed through a Durable Object instance, which is also quite near to the first user who opened the room.

Coordination of Updates

Y-Sweet uses a Conflict-Free Replicated Data Type (CRDT) for its Y.Doc data structure. As discussed in the RTC section, CRDTs are data structures that can be replicated across multiple systems, and they resolve conflicts in a deterministic manner without requiring any coordination. This makes them ideal for real-time collaboration scenarios where multiple users might be updating the same document simultaneously. Specifically, CRDTs allow concurrent updates that eventually converge to a consistent state, ensuring that all users see a consistent view of the document.

In the context of Y-Sweet and Cloudflare’s Durable Objects, each room in the application corresponds to a Durable Object instance, which maintains an in-memory state of the Y.Doc for that room. When a user makes changes to the document, these changes are sent to the Durable Object, which updates its in-memory state and broadcasts the changes to all connected users. This ensures that all users always see a consistent state of the document.

Asynchronous Persistence to R2

While Durable Objects maintain an in-memory state of the Y.Doc, we also persist this state to durable storage to prevent data loss in case of failures. This is where Cloudflare’s R2 storage comes into play. R2 is Cloudflare’s distributed, eventually consistent object storage system. It’s designed to be highly durable and available, and it’s integrated with the rest of Cloudflare’s global network.

The state of the Y.Doc is periodically persisted to R2 in an asynchronous manner. This means that the operation of writing to R2 does not block the processing of incoming updates to the Y.Doc. This approach allows the system to continue processing updates without being blocked by I/O operations, which contributes to the system’s overall performance and responsiveness.

Durable Objects provide strong consistency for their in-memory state, meaning that after an update operation is completed, any subsequent access will return the value of that update. On the other hand, R2 storage is eventually consistent. This means that updates to the data may not be immediately visible to all users, but they will eventually reach a consistent state. However, since the in-memory state of the Durable Object is always up-to-date, users will always see a consistent state of the document, even if the state in R2 is slightly behind.

In conclusion, the combination of Y-Sweet’s CRDTs, Cloudflare’s Durable Objects, and R2 storage provides a robust mechanism for ensuring data integrity in our real-time collaboration service.

While Y-Sweet and Cloudflare’s infrastructure provide a powerful combination for scalability and real-time collaboration, there are tradeoffs that we considered in our decision-making process:

Our adoption of Y-Sweet and Cloudflare’s technologies was a strategic choice to enhance our platform’s scalability and user experience. While we benefit from these advantages, we remain aware of the associated tradeoffs, such as increased costs, so we are committed to an ongoing process of refinement, and ensuring our scaling strategy is not only aligned with our technical objectives but also remains cost-effective.

Our goal in creating Umbra was to allow users not only to code collaboratively, but also to run their shared code and receive evaluated results back quickly. Deciding where to execute this code, and determining how to execute it safely, were two of our major considerations.

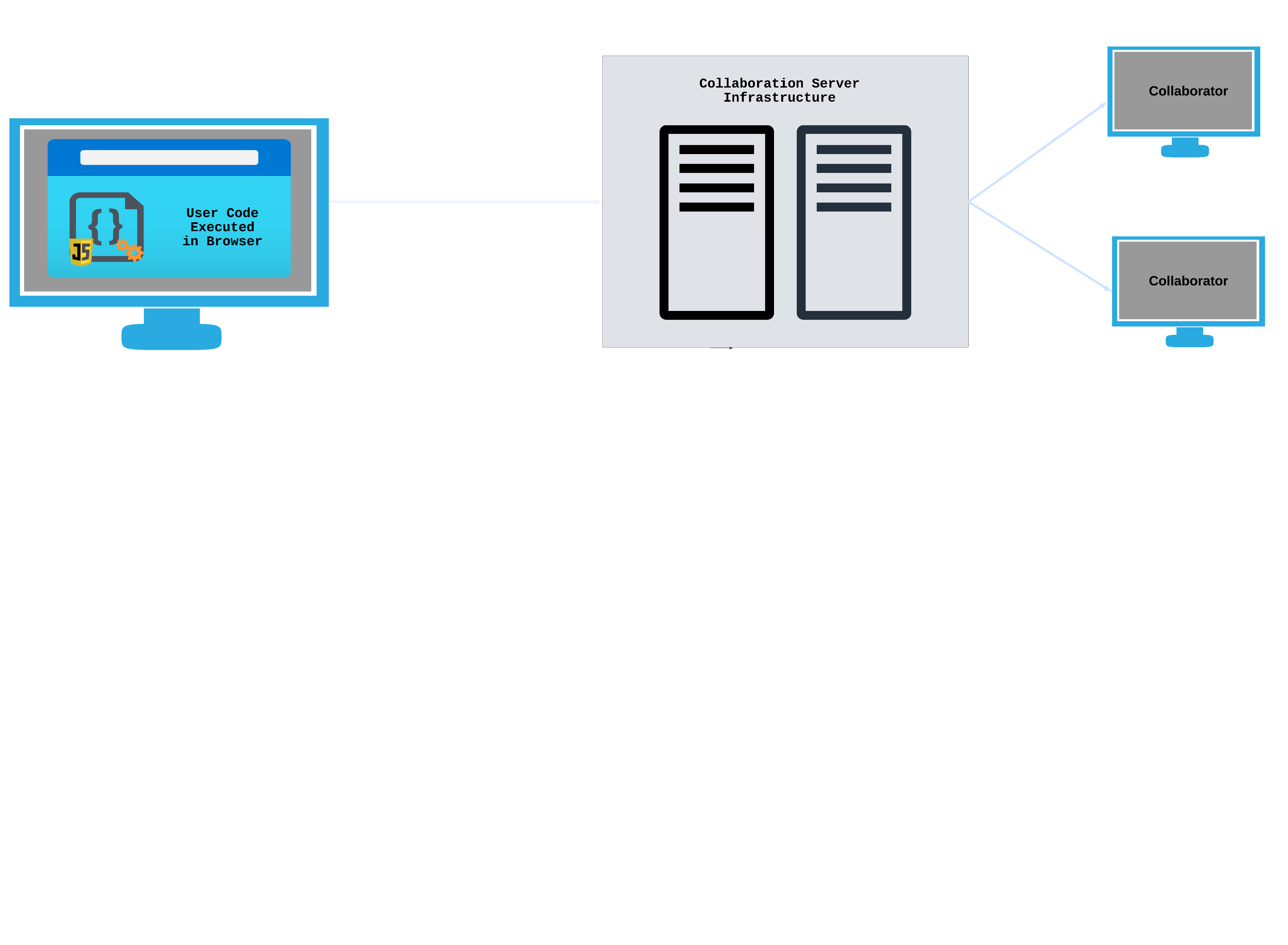

There are two broad options we considered when deciding where to evaluate the code submitted by users: in their own browser (client-side), or sent off somewhere else to be evaluated (server-side).

Either way, we knew we would need to sandbox the code execution environment. Sandboxing isolates external or untrusted code inside a restricted virtual environment, controlling its access to system resources. This prevents the code from accessing or even being aware of the underlying host system.

For instance, consider a JavaScript sandbox in a web browser

A web browser itself is already capable of evaluating more than just HTML and CSS. The ability of the browser to also evaluate JavaScript has been a cornerstone of the modern web, so why not leverage this existing architecture to evaluate user submitted JavaScript?

✅ No Network Round Trip for Code Evaluation

The user’s web browser is local to the machine they are using, so there would be no network trip to an external server to evaluate the code. This would reduce the latency experienced from the time of code submission to receipt of evaluation.

⚠ Web Browser is Partially Sandboxed

A web browser’s JavaScript runtime is sandboxed to a degree: the same-origin browser policy greatly restricts the ability for malicious code to do any damage beyond the user’s own machine. However, this sandboxing is not designed for executing arbitrary, potentially malicious code, and additional measures would be needed to ensure security. There are known methods to bypass the same-origin policy, and the web browser can’t limit the amount of CPU or memory a script uses to prevent resource depletion of the host system.

❌ Limited to Evaluating JavaScript/WASM

A web browser would only be able to evaluate JavaScript, and we were interested in allowing users to run code in other languages. It is possible to transpile code from other languages to JavaScript, or compile it down to Web Assembly, but this would involve extra processing steps and increase the users’ overall wait time.

❌ Reliant on Users’ Compute

Using client-side execution means putting more load on our users’ systems. It also reduces our ability to observe and control the execution performance; in the case that client side processing is slow, it will cause a lag for other connected users.

An alternative to executing code in the user’s browser is to evaluate the code on a remote server instead. This could be done on the same server hosting the Umbra web app, a separate server of our own set up specifically for evaluating users’ code, or a third party code evaluation service.

✅ Allows for Collaborating in Multiple Programming Languages

Having user-submitted code evaluated by a dedicated server process or third party API would allow users to collaborate in programming languages beyond JavaScript. We could support virtually any programming language by installing the correct compilers or interpreters on the remote machine.

✅ Controlled Code Evaluation Environment

Routing user submitted code to an external server would give us more authority over the execution environment. For example, we could set up logs to observe all execution requests; we could also exercise control with regards to security, including limits on memory and CPU usage.

❌ Possibly Greater Latency

When code has to travel to an external server for execution, it must take a network round-trip. For the user submitting the “run” request, this will result in a bit more latency in comparison to running the code on their own machine. (For other users, the difference should be negligible.)

❌ Potentially Dangerous Code

In the case of code being executed on the client machine, the code never has to leave the client’s machine. With server side evaluation, however, we open up the possibility for users to send destructive or malicious code to be executed on our servers, creating a significant security concern.

Ultimately, we decided on server-side execution. While either approach could work, having a server fully dedicated to properly sandboxing and executing code would help us create a better user experience by limiting the reach of destructive code, in addition to allowing us to support more programming languages.

The security issues involved with evaluating untrusted code are the focus of a vast amount of research and engineering. No method is ever 100% safe against attack, because attackers are always coming up with new ways to exploit previously unknown vulnerabilities in a system. For our purposes with Umbra, the focus was to reduce the space of vulnerability as much as possible, while weighing the tradeoffs of doing so.

Destructive code can originate from malicious actors, or from well-intentioned but inexperienced users. There are a few possible ways a bad actor can wreak havoc by exploiting a code execution environment that hasn’t been properly locked down:

In summary, allowing untrusted code to be executed on a machine means giving a stranger access to that machine. Proper safeguards need to be put in place to eliminate or minimize the ways in which the system could be compromised.

Despite the risks, executing untrusted code is a common occurrence. For example, it is a crucial business consideration for websites such as Coderpad, Leetcode, and CodeWars to protect their servers from potentially destructive user code. There are ways to minimize the potential for attack, and to ensure that the untrusted code can do zero or minimal damage to the underlying host system.

https://behradtaher.dev/2022/06/11/Sandboxing-Code-Execution/

One common method that we mentioned earlier is code sandboxing. There is more than one way to sandbox code, and different methods can keep the code more isolated than others, but all share the same goal of reducing the amount of harm untrusted code can do. Two approaches we considered using are virtual machines and containers.

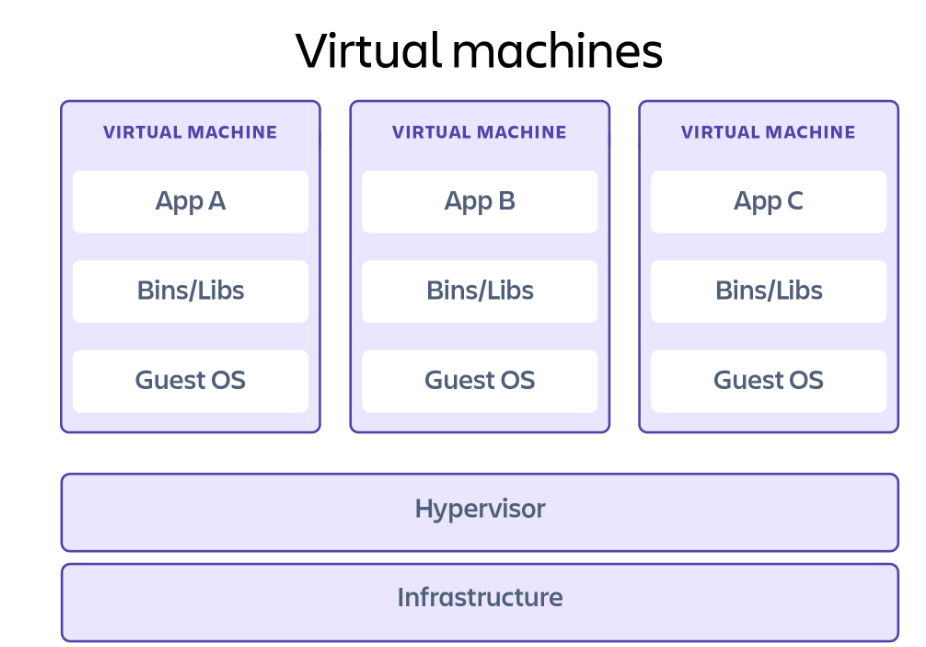

Virtual Machines

A virtual machine (VM) is essentially an entire computer system, with virtualized hardware and an operating system, that runs on top of the infrastructure of a host machine. Any code executed from within a VM is restricted to this environment. Without explicit access granted, it cannot access the underlying host. Any damage done is confined to this virtual machine, and handling the damage is simply a matter of deleting or resetting the VM.

Source: www.atlassian.com

Safeguards are still necessary to prevent access to network resources and the internet, but VMs alone are already a pretty secure way to isolate code. Exploits have been found where users can escape their VM sandbox and access the underlying host, but these exploits are generally found and patched very quickly.

Because a VM has to emulate both the hardware of a system and its OS, it does involve more overhead to load and run than some other sandboxing methods.

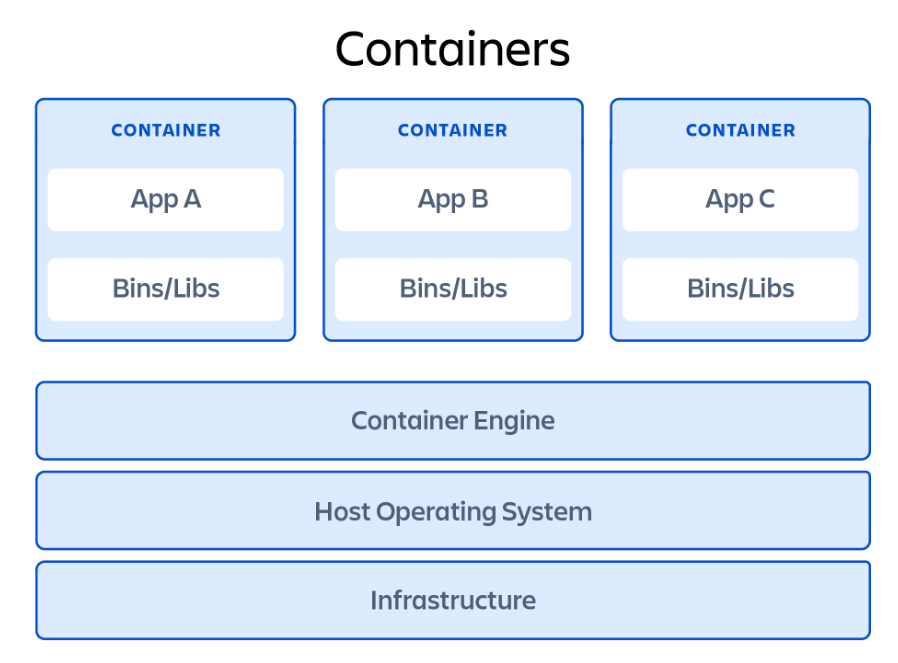

Containers

”Containerizing” untrusted code is a popular method of sandboxing, with Docker being a popular option. A container is similar to a virtual machine in that it sets up a virtualized environment for code execution. However, a container does not emulate hardware or an OS like a virtual machine does; instead, it shares the host operating system’s kernel.

Source: www.atlassian.com

This means there is less overhead work involved with a container, and it is generally lighter-weight and faster to start up than a VM. On the downside, containers aren’t as isolated as VMs because they share the OS kernel. Containers are also arguably easier to escape from than virtual machines, so there are generally additional safeguards to put in place.

Ultimately, we decided on server-side execution of user code. Having a server fully dedicated to properly sandboxing and executing code would give us greater security, in addition to allowing us to support more programming languages. Once we decided on this route, the next step was to choose between a number of possible options for server-side execution.

Deno is a JavaScript runtime that has gained popularity in recent years. In contrast to Node.js, by default Deno executes code in a sandbox that limits access to the underlying file system, the network, and environment variables. If the code requires access to any of these resources, then access needs to be explicitly granted at runtime. Deno also supports TypeScript out of the box.

For these reasons, Deno was a good initial choice for our code execution server. The way we set this up it was to have a designated server running a Deno process, and spawn child Deno processes from it. (A child process is a separate process that’s created by the “parent” process for the purpose of performing a specific task, and it runs independently with its own copy of the parent’s memory space.)

While this setup served us well initially, when we decided to expand Umbra to support languages besides JavaScript and TypeScript, we looked to alternatives. Our choice needed to have the same or greater sandboxing security that Deno provides, while also allowing us to expand our language offerings.

We researched various products that are specifically tailored to executing code in a safe environment. For example, Sphere Engine provides a closed-source commercial API that accepts code from a vast number of programming languages, executes it safely, and sends back the evaluated result. However, we wanted the ability to host the code execution engine on our own infrastructure, so we moved on to open-source options.

Judge0 is a popular open-source code execution system. It supports over 60 programming languages, and allows self-hosting. Beyond just code execution, Judge0 also provides mechanisms for testing code against expected results, and for this reason it is a good fit when “grading” code submissions is a priority, such as in online exams or programming contests. While the sandboxed security and expansive language choices were compelling, we decided it was overly resource-intensive for what we needed due to the additional grading functionality.

While looking at the various possibilities, we thought about what we would want in a code execution engine of our own making. In addition to sandboxing, we wanted more fine-grained control over the capabilities and permissions afforded to the untrusted code we were evaluating.

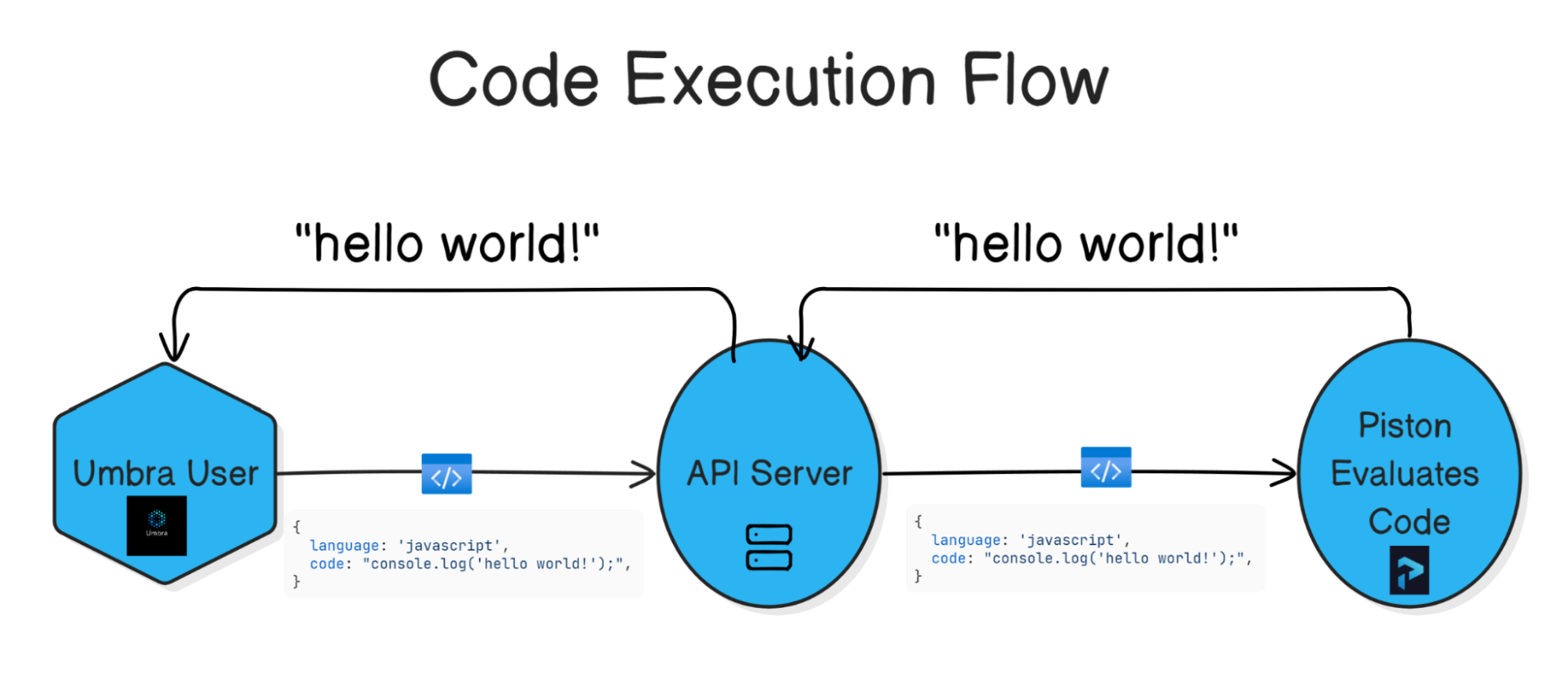

Researching with these considerations in mind led us to Piston, an open-source solution whose makers describe it as a “high performance general purpose code execution engine” with security measures built in. Piston is distributed as a Docker image, and uses containers as its principal method for sandboxing code. Beyond containerization, Piston also provides several additional security measures.

Within Piston’s Docker container, there is a Node API that accepts code execution requests and carries them out safely within the confines of the container. To do this, the API saves the source code to a file in a temporary directory, then compiles/executes the file.

The Piston API also allows the calling client to prescribe limitations on the maximum running time, compile time, and amount of memory used by any single code execution process. This provides a good amount of assurance against resource saturation.

Under the hood, Piston takes additional steps to reduce the risk of several common security threats:

stdout is 65536 per process.Code executions that surpass any of these limits are stopped with a SIGKILL signal to quickly end the process and prevent any further issues.

Writing our own code execution engine was something we had also considered doing. However, we decided to use Piston because we saw convincing evidence of prolonged efforts that have already been made towards securing it. Besides its creator, Piston has numerous other contributors, and maintains an open invitation for new penetration tests. We felt confident choosing it as the product of a concerted collaborative effort to find and eliminate code execution vulnerabilities.

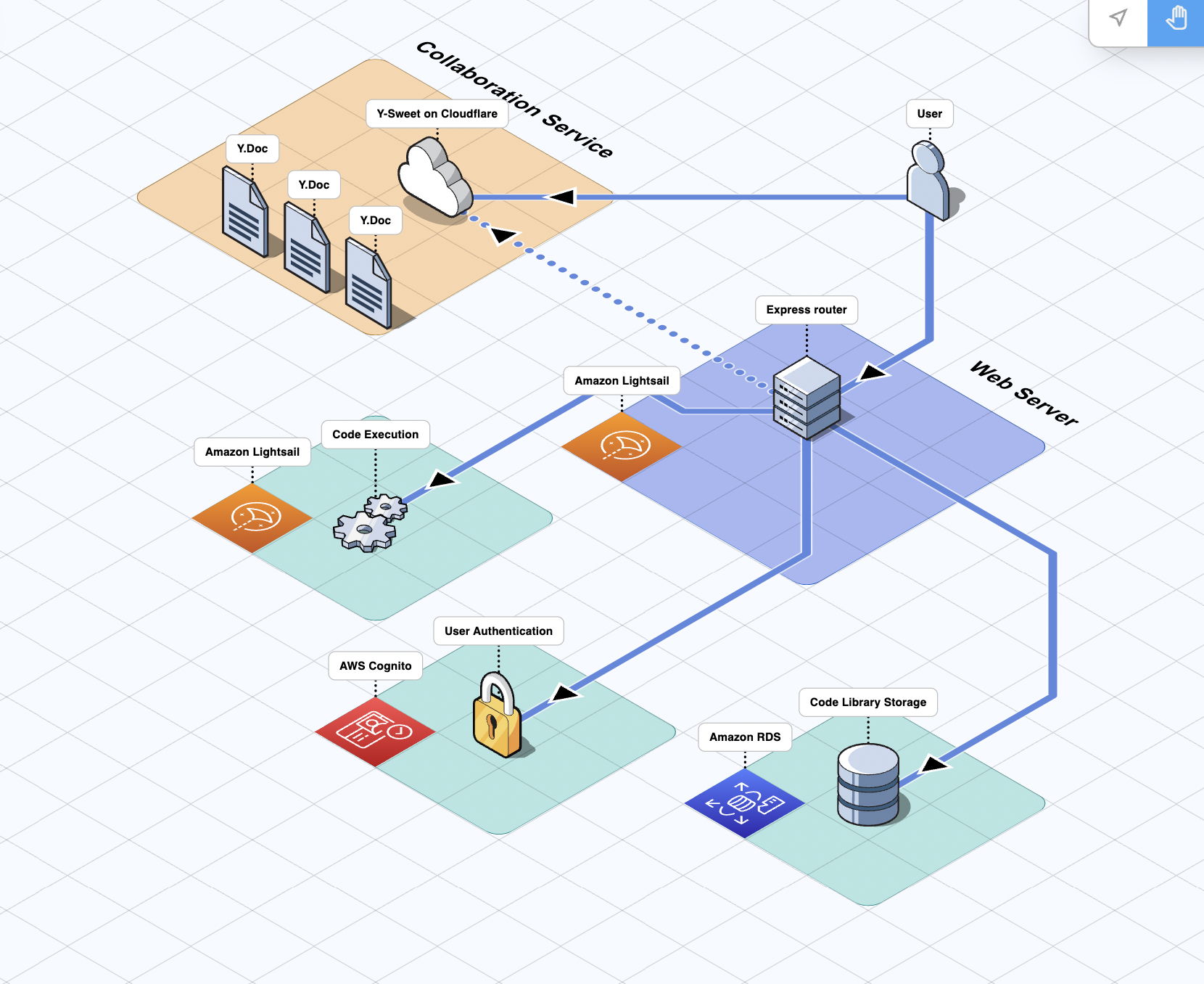

In this section, we will put all the parts together and take a look at our finalized system design, outlining the considerations that led to various choices regarding architecture, hosting, and infrastructure.

In designing Umbra’s architecture, we prioritized separation of concerns and scalability; the major functional components are served from their own dedicated nodes. The overall result is a service-oriented architecture that is flexible and loosely coupled: we wanted to ensure that as the application evolves, we can make changes to a particular service’s code or hosting infrastructure with minimal consequences for the other services.

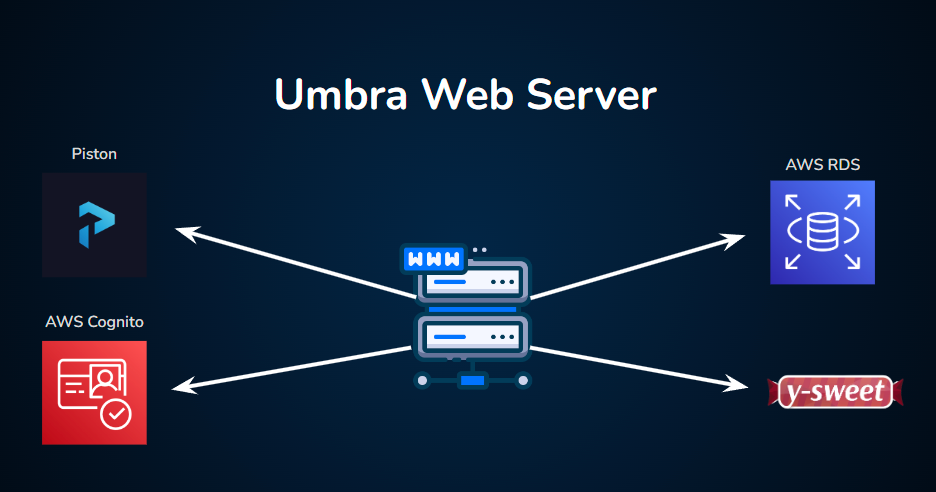

Umbra’s current deployment infrastructure

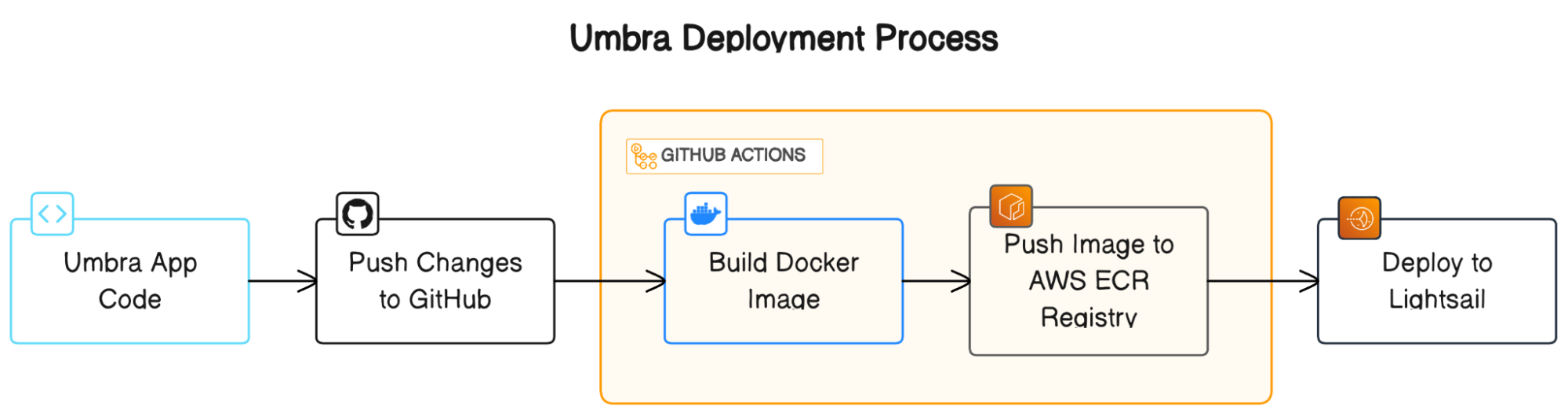

In order to facilitate flexibility and ease of development, all of Umbra’s (non-managed) services are containerized using Docker containers, and deployed automatically via GitHub Actions to their various hosting solutions.

All of Umbra’s non-managed services are currently deployed via AWS Lightsail, a cloud platform that is built on top of AWS Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2). AWS Lightsail streamlines some common tasks (such as deploying a container from Docker Hub) at the cost of decreased configurability.

During the development process, we experimented with a few different deployment setups. For example, we currently have alternative deployments of a majority of Umbra’s services on VPS instances (AWS EC2 and Digital Ocean droplets), which are less opinionated and more configurable. For now, though, Umbra’s main deployment is on Lightsail.

So far, the tradeoff of “less configurable” has not been a pain point. Instead, Lightsail has afforded us greater development efficiency by abstracting away concerns that we would otherwise handle manually, such as port mapping and SSL/TLS encryption. Additionally, Lightsail provides powerful and simple container deployment options, simplifying both manual and automatic container deployment.

In the following sections, we will explore Umbra’s service architecture in more detail.

The hub of Umbra’s backend services is the web server, which is responsible for routing and responding to HTTP requests to our website. For many requests, the web server will communicate with other services to develop an appropriate response to send back to the client. Here are the communication flows handled by our web server:

Code Execution

When a client wishes to run some code that they have written, the web server will send the code and its metadata along to the code execution service (our self-hosted Piston environment), which evaluates the code and sends back the results.

Code Library API

When a signed-in client sends Umbra a request to save a block of code to their Code Library, the web server uses Sequelize, an Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) library, to interact with our AWS RDS Postgres database. This interaction is facilitated through a REST API, which allows the server to fulfill the request by retrieving or saving code snippets as needed.

User Authentication

Another example of the web server’s role as our backend hub is the case of user signup and user authentication. For these tasks the web server will communicate with our authentication service, Amazon Cognito.

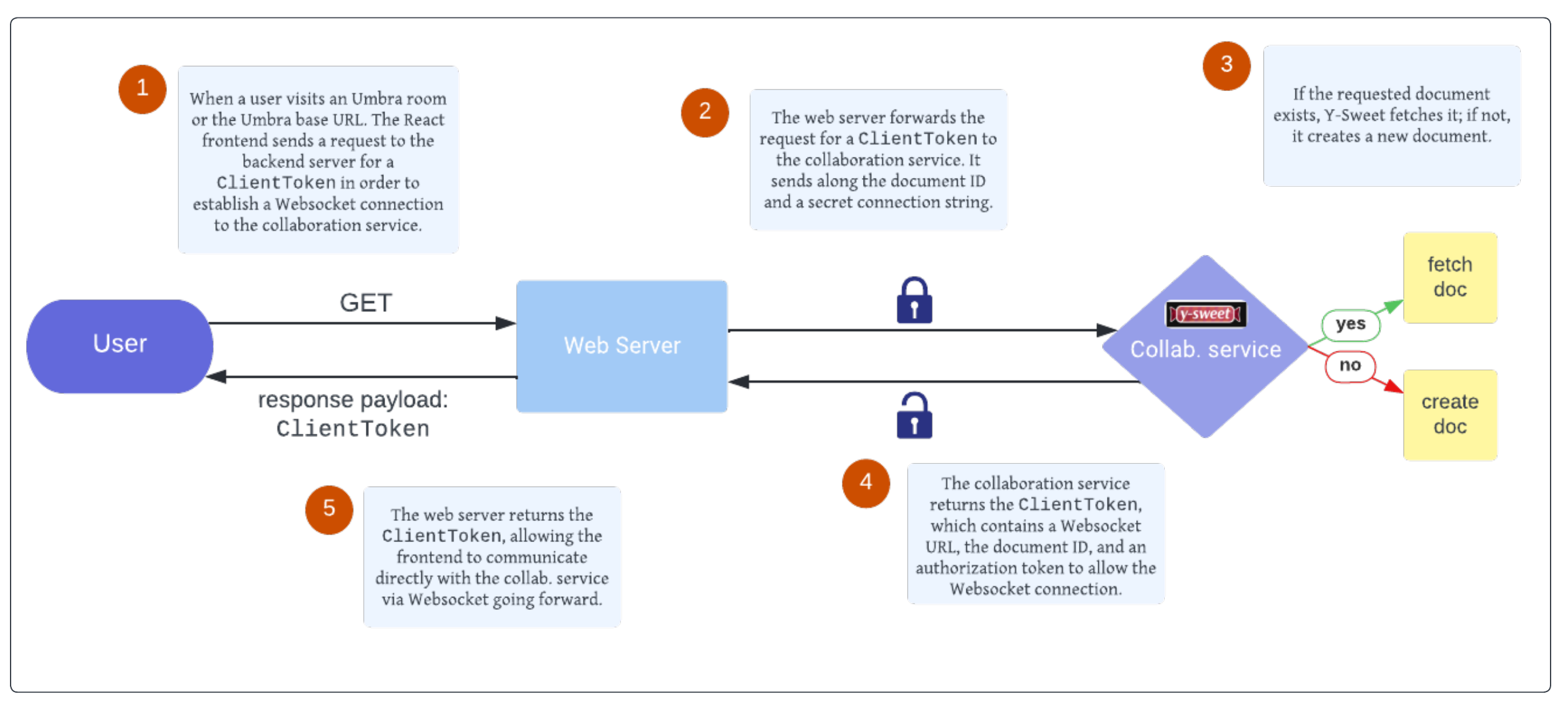

Brokering WebSocket Connections with Y-Sweet

The web server also brokers the initial connection between users and our collaboration service. In order to keep track of multiple WebSocket connections and clients, Y-Sweet issues unique client authorization tokens, similar to the way cookies are sometimes used in web applications. The web server is one of our services that is containerized using Docker and deployed to AWS Lightsail via Github Actions.

Umbra’s collaboration service provides its real time collaboration capabilities. This server’s primary responsibilities are scalably managing WebSocket connections, and broadcasting CRDT-based document data and awareness updates across all collaborating users.

Umbra implements this functionality by configuring Y-Sweet collaboration services to run on as many Cloudflare Workers as needed by load. Workers are Cloudflare’s Function-as-a-Service (FaaS) serverless execution resource, and Y-Sweet is designed to be hosted on this cloud offering. In order to save the document state of individual code editor pages, or “rooms”, there must be a way to persist data; for this, the Cloudflare Workers communicate with Cloudflare R2 for object storage.

For reasons of both security and scalability, code execution takes place on its own server. As described in 5.3 Current Deployment Choice: Piston, Umbra uses a general purpose, multi-language code execution engine called Piston that provides security and sandboxing features for running untrusted code.

Like the web server, the code execution server is containerized using Docker and deployed to AWS Lightsail. Right now it is deployed as a single node, but down the line we would scale it horizontally in tandem with the expansion of Umbra’s user base. We will discuss our analysis of scaling needs and system load in 7.1 Scaling Up.

User sign up, authentication, and authorization is handled with an AWS resource called Cognito. Given our service-oriented architecture and emphasis on separation of concerns, we wanted a discrete backend service for signup and authentication.

We chose to use AWS Cognito for two reasons:

Umbra’s “code library” functionality allows authenticated users to save blocks of code by persisting them to a PostgreSQL database. We opted to use Amazon’s Relational Database Service (RDS) to handle management of the database server.

While a NoSQL database could also have worked, Umbra uses a relational database to enforce a structured schema on a fairly simple relational dataset. The primary purpose of our database is to associate users with their saved code blocks. This schema structure is uncomplicated and unlikely to change, so we favored the schema-validation and ACID-compliance of a relational database over the flexibility of NoSQL.

As a managed service, RDS offers a number of features that were desirable for Umbra, but which could have soaked up valuable developer hours to implement ourselves. Among these features are automatic database backups, streamlined database administration, and vertical scalability via instance resizing.

While we feel our current iteration of Umbra is feature-complete with an eye towards our original goals, and our deployment infrastructure is enough to handle our current and estimated near-future needs, there are always things that can be improved upon.

As outlined in 3.6 Scalability Strategy, our horizontal scaling needs for collaboration are met by our deployment of Y-Sweet on a Cloudflare worker. We anticipated that this part of our infrastructure would be hit the hardest with traffic, as each user’s actions need to be reconciled with all other user’s actions within the same Y.Doc.

Our code execution server is the next area of our infrastructure that could require scaling up if user demand were to exceed our current server’s ability to process simultaneous code execution requests.

Currently, we have Piston set to handle 64 request processes concurrently. Each request has a maximum runtime of 3 seconds on the server, which means that within any 3 second period, we can handle up to 64 concurrent requests. Based on our current and anticipated usage of Umbra (~10-200 total concurrent users), this limit facilitates a great user experience with no noticeable impact to performance.

Should the code execution server need to be scaled up in the future, we are in a good position to do so. Our code execution server is isolated on its own node, which makes both vertical and horizontal scaling easier to accomplish. To horizontally scale, we would start by creating additional code execution nodes and employing a load balancer to route traffic between them.

Support For More Programming Languages

We currently support 5 of the most popular languages that appeal to a broad number of users, but support for more languages would expand the breadth of Umbra’s usefulness to more people.

Voice Chat

Our product doesn’t have any way for users to communicate with each other except for text within the Umbra code editor. The voice communication sector has many offerings already that people are accustomed to using, so we felt this wasn’t an important feature to include in our initial deployment. However, this could eventually be an intuitive feature for Umbra, and we are experimenting with a WebRTC implementation for it.

Embeddability

Given more time, we would be interested in making Umbra’s coding environment an embeddable component that could be used in websites and within other collaborative applications.

https://websockets.spec.whatwg.org/#the-websocket-interface

https://webrtcforthecurious.com/docs/01-what-why-and-how/

https://developers.cloudflare.com/r2/

https://mattweidner.com/2022/02/10/collaborative-data-design.html#list-crdt

https://www.tag1consulting.com/blog/yjs-deep-dive-part-1

https://docs.yjs.dev/api/internals

https://www.bartoszsypytkowski.com/yata/ (YATA is what Yjs uses)

https://blog.kevinjahns.de/are-crdts-suitable-for-shared-editing/

https://josephg.com/blog/crdts-go-brrr/

https://discuss.yjs.dev/t/compliance-limitations-on-data-retention/537

https://github.com/yjs/yjs/issues/415

https://discuss.yjs.dev/t/scalability-of-y-websocket-server/274/8

https://github.com/erdtool/yjs-scalable-ws-backend

Robert Miller, “Response time in man-computer conversational transactions” AFIPS ‘68 (Fall, part I): Proceedings of the December 9-11, 1968, fall joint computer conference, part I – December 1968 Pages 267–277 ↩︎

David Dickinson

California

Fred Durham

Texas

Michael Johnson

Oregon

Bethany Pietroniro

New York